Alice Leung Does Stochastic Tinkering

I noticed Alice Leung tweeting about tinkering with the configuration of her classroom:

There developed a lovely conversation between her and @sarahjohanna :

Now I really resonated with what was going on here and what I often notice in Alice's tweets: a constant energetic questioning and tinkering, and then reflecting on the results. Apart from anything else, I just want to shout a hearty 'hear hear!' and celebrate the moment.

The exchange also sparked some associations and I've thrown them here below:

"Stochastic Tinkering"

I picked this lovely phrase up from Nassim Taleb in his books "The Black Swan" and "Antifragile". By stochastic he means random. For me, the word has connotations of deliberate intent to shake things up... staccato stabs at innovation.

Stochastic tinkering isn't far off notions of edu-hacking.

Taxonomy of Frames

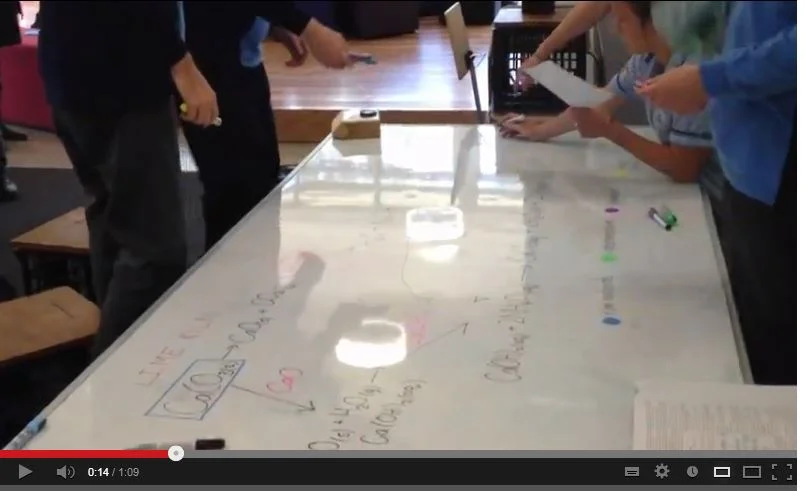

In my 'frames' taxonomy for innovation, Alice is tinkering with "o-frames" - organisational frames. In this case, they are the physical frames in her learning space, consisting of furniture, empty space, etc, within the broader o-frame of the classroom building itself.

Alice observes that "HS teachers don't really think about learning space layout".

My aspiration for the 'frames' taxonomy is to expose these arbitrary elements and make them more susceptible to innovation. Alice, of course, does this instinctively.

Frames are for edu-hacking, stochastic tinkering.

Design Thinking vs Hacking

I've noticed Design Thinking is getting more and more traction in educational circles. Indeed I myself have become rather besotted by it. I suspect that within a year or two it will have the same horrible simplistic buzz word status as flipped learning, PBL, gamification.

All these models wander in and out of the edu-zeitgeist.

As much as I love Design Thinking, I wouldn't want it to become a dogma to replace "fly by the seat of your pants" hacking/tinkering.

So much of life, experience, and nature, and everything is composed of ad-hoc tinkering.

Hacking is immediate, contextual, empowered, and subversive! It provides its own research data, because it either works immediately & sticks or it doesn't and doesn't.

A blog post contrasting Design Thinking with hacking is here, with lots of further links.